A fertile valley on the Peloponnese peninsula has become the site of the main ancient festival – the Olympic Games. They were held in memory of the battle of the two gods, but against the background of the Greek “sacred world”.

THE FOUR-YEAR CYCLE OF THE CURRENT OLYMPICS, which began in 1896, was interrupted by world wars, overshadowed by terrorist attacks and political boycotts. These games were resurrected as a symbol of peaceful competition of countries represented by their best athletes. However, the atmosphere of international intrigue around the main sports competitions of our time fully corresponds to their difficult centuries-old history.

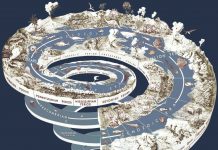

Ancient Greece was never a single state — it was torn apart by bloody civil strife every now and then. However, once every four years in July, all wars were interrupted by the “sacred peace”. For more than 1000 years — from 776 BC to 394 AD — the Greeks united in a single, common desire for physical perfection.

The monument to this ancient sports festival is the ruins of Olympia, a town in the fertile Peloponnesian valley, washed by the river Alpheus (Alfios) and its tributary Kladei.

A PLACE CHOSEN BY THE GODS

Excavations show that this place has been sacred since prehistoric times. Then the city became the center of worship of the main of the gods — Zeus. According to legend, he initiated the Olympic competitions by fighting here with his father for power over the world. Then other immortals measured their strength here.

Apollo boxed with the god of war Ares and ran races with the god of roads, trade, pastures and herds (and the patron saint of thieves) Hermes. Olympia became a place of divine duels, the rules for which were established by the mighty Hercules.

The Olympiads for ordinary mortals began in 776 BC with a celebration at the temple of Zeus in honor of the conclusion of peace between the kings of the neighboring cities of Elida and Pisa. Running competitions were held, in which the Elid cook Koreb won. Then the names of the Olympic champions began to be recorded in the annals: the chronology of other historical events was tied to their records.

FIGHTS WITHOUT RULES

Having declared a military truce for the duration of the games, the city-states gave vent to passions in uncompromising sports duels. The main competitions” were running, fist fighting, wrestling and their combination – pankration (see the image on the vase), where almost everything was allowed. The winners of the Olympiads enjoyed exceptional honor and respect – their sculptural portraits were placed next to the statues of the gods.

Over time, chariot racing, jumping, discus and spear throwing and running with weapons appeared in the program of the games. By the 5th century BC, the Olympiads had become the main Greek festival with a clearly established program of holding.

Despite the peace, the control of the games created strong friction between Elida and Pisa. By about 700 BC, the conflict had escalated so much that all Greek states pledged not to wage wars during the Olympics — a tradition that persisted for more than 1,000 years before the ban on these competitions. Trials and execution of death sentences were also suspended. To fight during the games and a month’s preparation for them was sacrilege, fraught with serious sanctions.

PREPARING FOR THE HOLIDAY

The organizers of the games were the residents of Elida, who took the matter seriously. For several months, in order to announce the opening day, messengers were sent to all Greek cities and colonies, up to the Crimea. Judges and managers — ellapodics were chosen from the Elidians, who monitored compliance with strict rules not only at competitions, but also before they began.

After learning about the opening day, applicants for participation started home training, but arrived in Elida for registration a month before the games. In recent weeks, they have been training under the supervision of the Hellenodics according to their established program. For violating the regime, they were flogged with rods.

Only free men and boys of purely Greek origin were allowed to compete — this moment was carefully checked. The rule was relaxed after the submission of Greece to Rome — its citizens also began to participate in the Olympics. Women were forbidden to participate in the Olympic Games even as spectators.

While the Olympians were training, the roads leading to the secluded valley where the Games were to be held were filled with pilgrims. Their safety was guaranteed by the “sacred peace” pleasing to Zeus.

Many walked, sleeping under the stars. The rich rode on horseback or in chariots. Those arriving by sea went ashore at the mouth of the Alpheus River and followed up the sacred river by the shore. There were many acrobats, magicians and musicians in the crowd. Women were generally forbidden to appear on the “Olympic” side of Alpheus during the five days of the festival.

The first of the days was devoted to the opening ceremony — the sacrifices and the oath of the participants. The main sacrifice was offered on the altar of Zeus Gorki, i.e. the Oath-Bearer. The organizers, athletes and their families gathered in the Bulevteria, a building built in the VI century BC. A wild boar was slaughtered here in front of the statue of the god. Over his carcass, each participant swore that he was clean before the law and would not violate the Olympic rules. A liar or perjurer was fined and disqualified for life.

Modern Olympiads begin with the lighting of the sacred fire, delivered to the host country from Olympia by a relay of runners (and other means). The exact schedule of the ancient games is unknown, but the fire ritual was also present there. On one of the five days, a solemn procession of Hellenodics in purple robes entered the stadium to the sound of trumpets. Athletes followed her. Flames flared up on the sacrificial altar.

On the second day of the Olympics, the audience stood up with roosters to take the best places. The countrymen stuck together.

FAME AND RISK

The program of the competitions included running, wrestling, fist fighting, discus and javelin throwing, running with weapons, chariot races. Everyone, except the drivers, performed naked – the Greeks appreciated physical beauty. There were no team competitions — everyone won individually, but shared the glory with his hometown.

Riders and chariots competed at the hippodrome – an arena 706 m long south of the main stadium. The horses were held at the start by a rope stretched across, which was removed at the signal of the pipe. The riders used only a bridle, they had no saddle or stirrups. The victory was counted to the animal, even if it finished without a rider.

Such a case occurred with the mare Aura, who led the race from the very first minutes, dropping the “extra load”. Its owner, the Corinthian Feidol, was declared the winner, and a statue of his horse was erected in Olympia.

Chariot racing was a dangerous sport. The driver whipped four horses with a whip (later a couple), making 12 laps on a bumpy track on a springless gig. Accidents were in the order of things, and only the drivers of the extra class managed to fit into sharp turns at high speed, maneuvering between broken chariots, running horses and fallen bodies of rivals.

STRENGTH AND AGILITY

In the fight, it was necessary to put the opponent on the shoulder blades three times. Knowledge of techniques and the ability to keep balance meant no less than brute force here.

However, she was certainly welcomed. One of the most famous Olympians of antiquity, five-time wrestling champion Milon of Croton (from the south of Italy), became famous for his demonstration performances, including the ability, by contracting muscles, to tear the rope tied around his head. When the aged athlete lost his sixth Olympics, the crowd ran out to the stadium and carried him around the circle of honor to a general ovation.

In a fist fight, the hands were tied with leather straps, but the thumbs remained free. They fought without a time frame, until someone gave up or fell down without strength. Ego was an endurance test.

A combination of fist fighting and wrestling was pankratioi. Here it was not allowed only to bite and squeeze out the opponent’s eyes. The spectacle was not for the faint of heart. The ground cleared of stones was watered with water, and the bloody athletes were lying in the mud, twisting each other’s joints, punching and kicking.

The fight was fought until someone admitted defeat. However, killing was not encouraged and was considered a lack of skill.

We ran three distances: sprint, from end to end of the stadium (stage 1 = 192 m); diavlos – at stage 2; dolichos – at stage 24 (approximately 4.6 km). The marathon was introduced only at modern Olympiads in honor of the legendary war messenger Phidippides, who ran non-stop in 490 BC about 40 km between the Marathon and Athens, reported the victory of the Greeks over the Persian (Iranian) landing and immediately died.

The starting line of the stadium in Olympia, designed for 20 athletes at the same time, has been preserved. First there was a qualifying long run, and then 2 short ones. The starting pads are stone slabs dug into the ground with two parallel furrows, from which the toes of bare feet were pushed off. Instead of a shot, a trumpet sounded or just a shout: “Apite!” (“March!”).

In addition to three light races, there was a fourth, at stage 2, “in full gear” of a heavily armed Greek infantryman (hoplite).

The most Greek of the ancient Olympic competitions can be considered a pentathlon, i.e. pentathlon. It included running, long jump, discus throwing, javelin throwing and wrestling. Obviously, this required strength, speed, flexibility – harmonious physical development, the ideal of ancient Greece.

The disks were made of stone or bronze. The Olympic ones have not been preserved, but other Greek specimens of that era weigh up to 6.6 kg with a diameter of 15-23 cm.

Olympic champion Favl threw a discus on the 29th . Now this record is covered more than twice, but with discs weighing 2 kg. It looks like the ancient discobols did one swing back, bent over, and then three-quarters of a turn. Now, before releasing the projectile, they rotate around their axis two and a half times.

As for the spear— it is not clear what was valued: distance or accuracy. A belt loop was attached to the shaft, which was hooked with the index finger, giving them an additional push to the projectile. Similarly, the sling strengthens the stone throw.

They jumped in length, apparently from a place, five times in a row, to the flute, which sets the rhythm of movements. The jumper held stone or lead dumbbells in his hands, waving them to give himself momentum.

NEAR – SPORTS LIFE

The Olympic celebration unfolded not only at the stadium and the racetrack. The gathered crowds walked day and night. Peddlers sold wine and honey cakes, trinkets, amulets, images of gods. An extensive audience was gathered by speeches of demagogues and official competitions of poets and speakers. A lot of them flocked here to show off their talents and attract new students.

In Olympia, the philosopher Plato (428 or 427-348 or 347 BC) spoke to the crowd, and the historian of the fifth century BC Herodotus became famous by reading chapters of his writings. Here, in 380 BC, Isocrates presented his treatise “Panegyric”, calling on the Greeks to unite.

On the last day of the games, the winners were announced and awarded. The prize itself was purely symbolic, but each champion (Olympian) was waiting for a loud lifetime fame. The crowd listened in reverent silence to his name, his father’s name and the name of his city. Then he received a wreath of the leaves of the sacred olive tree, which, according to legend, was planted by Hercules himself.

At the end of the ceremony, the procession of Olympians, Hellenodics and whitewashed horses went to Altis – the sacred sycamore grove at the foot of Mount Kroi. These trees were also allegedly planted by Hercules.

Особую славу стяжали периодоники — победители не только Олимпиады, но и всего цикла греческих спартакиад.

AWARDING THE CHAMPION

At the Greek Olympiads, second and third places were not recognized: there was a single prize-winner in each sport.

The champion was greeted with jubilation by the whole native country. Sometimes a grandiose performance was arranged: a part of the city wall was dismantled for the entrance of the hero — the gates were for ordinary travelers.

EQUAL TO THE GODS

Many champions have participated in the games for decades. Theogenes of Phasos, the invincible wrestler of the V century BC, performed for 22 years, receiving wreath after wreath. Fame made him literally immortal — he was proclaimed a descendant of Hercules. Since the beginning of the IV century BC, Theogenes was revered as a god.

The religious coloring of the championship is not surprising, given the mythologization of ancient Greek consciousness. Athletes’ physical abilities were considered a divine gift: Zeus helped those who deserved it – with a healthy lifestyle and hard training. “Victory will not come without effort, that crowns our merits and adorns life,” the lyricist Pindar sang.

Statues of the victors and gods stood side by side in the Olympic sanctuary. Once there were at least 200 such sculptural portraits. In 430 BC, the Athenian sculptor Phidias made a 15 m high statue of Zeus out of gold and ivory for Olympia. The jeweled colossus became one of the Seven Wonders of the World.

THE END AND REBIRTH OF GAMES

Zeus and his champions were honored a few days after the games, which ended with a feast for athletes and honored guests in the Prytanea (City Council). Then the crowds dispersed. Tents and stalls were being rolled up. Spectators, merchants and peddlers returned to their native lands, and peace again descended on the sacred Olympia.

After the conquest of Greece by the Romans (in 146 BC), the program of the games almost changed. In 65 A.D., the Emperor with a Pen insisted on the inclusion of musical and dramatic competitions in it. He himself participated in a chariot race, driving a dozen horses. True, he fell and left the race, but still received an olive wreath. At 68, he committed suicide, and this shameful 211th Olympiad was erased from the annals.

However, the Romans rarely disrupted the course of the games until 394 AD, when the God-fearing Christian emperor Theodosius I banned them, declaring them a pagan relic. The earthquakes of the VI century led to floods that brought Olympia with an almost five-meter layer of silt.

The site remained relatively untouched until large-scale excavations began in 1875. Inspired by sensational discoveries, the French sports enthusiast Baron I Pierre de Coubertin in 1894 at the International Sports Congress achieved the resumption of the Olympics as a symbol of peaceful rivalry of nations. 13 countries participated in the 1896 Games, and about 200 participated a hundred years later. The number of sports was also growing. Until 1924, the program of the Games included only summer sports (although hockey and figure skating were sometimes included). In 1924, the independent Olympic Winter Games were held for the first time in Chamonix (France).

Over the recent history of the Olympics, it has been repeatedly overshadowed by wars (because of them, the Olympics of 1916, 1940,1944 were canceled), partial boycotts (1980, 1984), hostage-taking…

In 1916, the Olympic Games were to be held in the capital of the Russian Empire, St. Petersburg, but the World War prevented it.

It remains to be hoped that the Greek example will help us find the way to eternal “sacred peace”.

In honor of the champion’s return, a grandiose performance was arranged: a part of the city wall was dismantled for him — the gates were for ordinary travelers.