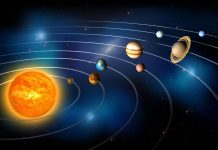

In 1233, the gaze of the grand master of the Teutonic Order turned to the east, where in the darkness of paganism, peoples vegetated on almost deserted fertile lands. Brave blond knights brought the light of the true faith there, followed by German colonists to the liberated territories. On September 1, 1255, the fortress of Konigsberg was founded on the site of the ruined Prussian settlement of Tvangeste. Villages and craft settlements quickly grew up around it. Adherents of the secret sciences were not slow to join the conglomerate of hardworking villagers: astrologers, alchemists, mystical philosophers and healers, whose hobbies, different from Christian dogmas, were persecuted in Western Europe as heresy and witchcraft.

Perhaps the grandmaster of the Catholic order represented the new city differently, but away from the German villages and towns with their established customs of persecution of dissenters, wizards and magicians felt very at ease. With their active influence, Konigsberg was formed as one of the most tolerant Christian cities to engage in occultism. Even the proximity to the main temple – the Cathedral – did not prevent the enchanted quarters on the banks of the Old Pregel from flourishing and developing.

The “policy of untied hands” has done its job. In the XIV century, the alchemists and fortune-tellers of Kneiphof (now the island of Kant) were reputed to be the most knowledgeable in Europe. Realizing the importance of the acquired knowledge and the power of necromancy, warlocks resorted to a fanatical means called “Ludwig’s nail”. A nail was driven into the forehead of the deceased sorcerer, piercing the skull, pillow and boards.