In the first half of the XIX century, a new miracle of technology appeared to mankind – photography. It struck people’s imagination almost more than, say, the Internet or cellular telephone communication today. Enthusiasts quickly moved the new business forward. The masterful works of photographers – these new artists – captured for posterity many events of political, social and cultural life, including tragic events.

Among the ardent adherents of photographs was the English Queen Victoria. As an example to other royal houses in Europe, she established the position of a court photographer and invited one of the enthusiasts of the new art, Roger Fenton.

He was born in March 1819 in Crimblehall, Lancashire, and was the second child in the family of John Fenton, an entrepreneur, banker, and member of Parliament. Roger began his studies at University College in London. He received his first drawing skills from the famous historical painter Charles Lucky, and from 1841 to 1844 he studied drawing and painting already in the Paris studio of the popular French artist Paul Delaroche. Another famous artist-photographer Gustave Le Gray also worked in this studio.

When one day Roger Fenton saw the works of the first photographers, he immediately and forever preferred photography to traditional fine arts. And Delyarosh himself “added fuel to the fire”: he turned out to be the one who, after seeing the first degerrotype, exclaimed: “The end of the drawing, he is dying!” After finishing his studies in the studio, completely surrendering to photography, Roger Fenton joined the “First English Photographic Company”. Later he became secretary of the London Photographic Society. In 1847, he married Grace Maynard, they had three daughters, two of whom, following their father’s example, became interested in photography.

Roger soon achieved high mastery in his photographic works. It was then that he was noticed by the Queen. She wanted to make him her family photographer as well. Fenton filmed the daily life of the royal family, and solemn processions with the participation of the highest nobility, and palace interiors, and parks, and the architecture of London. He showed great skill and taste in the genre of portrait photography. His models were many high-ranking officials of the state, writers, artists.

In 1852, Roger Fenton took his art photographs to an exhibition in Russia – he visited Kiev, St. Petersburg, Moscow. He was successful everywhere. And in March 1855, Queen Victoria sends her best photographer to the Crimea, where at that time there is a bloody war – the Anglo-Franco-Turkish coalition against Russia.

Fenton arrived by ship in the bay of the Tatar city of Balaklava, near Sevastopol, together with assistant I… with his personal chef. In all likelihood, the photographer suffered from some kind of intestinal disease. In a narrow bay, ships were crowded in disarray, close to each other, so that we had to wait almost a whole week to approach the shore and unload considerable “luggage”: three horses, a wagon-wagon and 36 huge boxes, where five cameras and 700 glass plates rested. Roger Fenton himself designed a steam-horse “photographic van”, which served as a photographer’s laboratory, kitchen, and bedroom at the same time.

Photography in those days was still a very troublesome and technically imperfect business. The method of “wet collodion” came into general use. The essence of it was as follows. A layer of collodion (a special adhesive substance) was poured onto the polished and degreased glass surface and immediately placed in a silver salt solution, where it acquired the property of photosensitivity. It was necessary to remove and develop it until the collodion dried up. The hypersensitivity of such a collodion emulsion was rather weak, and this required exposure from tens of seconds to several minutes. It is clear that the subjects of the shooting had to be stationary.

For four whole months, Fenton prowled around the battlefields in his “photographic van”, filmed the places of the most stubborn clashes of opponents, groups of soldiers in combat positions and bivouacs, made portraits of commanders, beautiful Mar-Chinese women. At the same time, he competed with the battle artists attached to the shelves. As a photographer of the Queen, he was assisted by the command, he was greeted everywhere with friendliness and interest. But the working conditions were still “worse than ever.”

The oppressive heat was in the dark room on wheels, the collodion dried quickly, the water in the washing tanks almost boiled, and evil heavy flies burst into the room, only briefly opened the door for ventilation. Nevertheless, Fenton managed to produce 360 high-quality prints, which he brought to London at the end of June. An exhibition of Fenton’s works was held in the gallery of the Watercolor Painting Association. The author was not present at the opening. He felt very ill, exhausted and exhausted. Queen Victoria and her husband Prince Albert visited the master.

Roger Fenton’s photo reports on the Crimean War were greeted with delight everywhere. In part, this success was prepared: the photographer sent several pictures from the Crimea in advance and they were published by the London Illustrated Newspaper. In August, the Queen and Prince Albert went to visit their ally, the Emperor of the French, Napoleon III, and “took” Fenton with them. In the residence of Saint-Cloud near Paris, the emperor spent two evenings smoking cigarette after cigarette, looking at the pictures with the keenest interest and listening to Fenton’s story. At the beginning of January 1856, the first military photojournalist spoke at a meeting of the London Photographic Society with a report on his work in the Crimea, showed drawings of the cameras he used, described the process of developing and fixing plates and prints.

Once again, Roger Fenton came to the Crimea in the late spring of the same year and almost immediately returned to England. Russian troops then heroically repelled the desperate assault on Sevastopol. The war lasted all summer and ended in September with the capture of Malakhov Kurgan by the forces of the interventionists. In the last battle, over twenty thousand people were killed on both sides.

Two other British amateur photographers, James Robertson and Colonel Charles Langley, told about the final phase of the war. The first, a coiner by profession, was on his way to Constantinople to take up the post of director of the mint there, but… he deviated from the route, reached the Crimea and managed to capture on photographic plates the consequences of the war and Sevastopol lying in ruins, abandoned by the defenders by the decision of the Russian command, but not defeated. The second photographer was in Crimea only in November. Sevastopol was already healing the wounds of the war: streets were being cleared, houses were being restored. Langley, an enthusiastic amateur photographer, asked to delay the disassembly of the most spectacular, from his point of view, ruins. He really wanted to take impressive pictures. They went to meet the Colonel.

So, the well-known photo reports about the Crimean War mainly belonged to the three named photographers. Over time, it turned out that the British government had secretly sent a photographer by the name of Niklin and two assistants to the Crimea even before the campaign began. These people were carrying out a reconnaissance mission – to photograph the Sevastopol fortifications. By chance, the photo survey did not take place. The Daily News newspaper reported on a shipwreck in a severe storm, in which the spy photographer, along with his assistants and all photographic equipment, died.

The authors of military photo reports worked on the battlefield on the orders of the authorities in power. Accordingly, the tasks set for the photographers were quite definite: to show skillful and wise military leaders developing brilliant combat operations, valiant soldiers and officers, exemplary organization and equipment of the army… In other words, everything that would inevitably lead the coalition to victory. However, the coalition’s victory did not take place. The then Russian Foreign Minister Prince Gorchakov wrote that “at one of the most tense moments of the war, at a meeting of representatives of the highest command circles of the warring countries, it was decided to stop the unprecedented and senseless bloodshed.” Thus, the conflict ended through peaceful negotiations and the conclusion of the Paris Agreements.

As for the population of the coalition countries, according to the plans of their governments, photo reports about the war were supposed to awaken patriotic feelings and respect for the powerful in people.

But, in addition to the will of the photographers, who conscientiously and professionally performed the tasks, the whole world for the first time so clearly saw the repulsive face of the war, devoid of brilliance and parade.

Both Fenton and Robertson, and even the military man Langley – a participant in the battles against Napoleon Bonaparte back at Wagram and Waterloo – showed in their masterfully executed photographs the tough battles of the warring armies, the suffering of people doomed to injury and death, the destruction and desolation of the land, still intended for a peaceful and happy human life.

As for the professional problems of photography, it is impossible not to admit: the reports have greatly advanced the technique of filming itself, processing of the captured materials, and the development of portrait photography, sons Viktor and Alexander became correspondent photographers. The elder, Victor, was sent to Manchuria by the authorities in 1904 to the theater of operations of the Russian-Japanese War that had begun. The technique of photography has gone far ahead in comparison with the times of the Crimean War. Victor Bulla’s reportage photographs, taken half a century after Fenton, conveyed pictures of the fighting vividly and dynamically.

Subsequently, Viktor Karlovich filmed episodes of the First World War, the events of both revolutions of 1917, the leader of the world proletariat and his associates, the formation of the Red Army and Navy, the construction of power plants and other industrial facilities. Exactly 132,683 negatives with the most valuable information were transferred by the photographer to the state archives…

In 1938, on the false denunciation of Viktor Karlovich, Bulla was arrested. Relatives were informed: “Enemy of the people. Exiled to the DVK (Far Eastern colony). Ten years without the right of correspondence.” Prominent politicians and reputable scientists recognized the great historical and artistic value of Victor Bulla’s photographs, but they could not help to rescue him from prison. He died in 1944 from stomach cancer in one of the GULAG camps. In 1958, Bulla was fully rehabilitated. But nevertheless, fatography as a fine art.

War reports by British photographers have stimulated the enthusiasm of photographers in other countries, in particular in Russia. A family of photographers by the name of Bulla worked in St. Petersburg.

The head of the family, Karl Karlovich Bulla, a native of Germany, after long and persistent efforts, overcoming bureaucratic obstacles, in March 1886 received an official certificate that “there are no obstacles on the part of the police to take photographic views of the capital and the surrounding area… provided that there is no congestion of the public and crews.” Since that time, the Bulla family’s photo studio has been flourishing, gaining the widest popularity both in the capital and abroad. The father of the family was more occupied by Milia, this was not mentioned anywhere for another twenty years. The photographer’s pictures were published anonymously. In the end, the authorship of many well-known photographs was revealed. One of them is “The shooting of the July 1917 demonstration in Petrograd.”

The Japanese company “Kasio” has created the world’s flattest camera. The thickness of the digital camera is only 11 millimeters. In size, it is quite comparable to a credit card and, as the creators say, fits in a business card box. A 100-gram eight-by-five centimeter camera with an electron-optical converter of 1.5 million pixels stores up to 500 photos in memory. The shooting speed of one frame is one and a half seconds. The camera appeared on Japanese shelves in July 2002, and on the international market a year later. Its price was about $ 300.

In the same Japan, the world’s first binoculars with a built-in camera appeared. The creation of a unique hybrid was announced by the company “Asahi kogaku kogio”.

The optical device with a sevenfold magnification is equipped with a digital camera capable of “snapping” up to 800 thousand photos. All you need is to focus and press the button.

The creators say that the development is especially convenient for those who like to watch wildlife. It is also possible that it will be adopted by employees of security and detective agencies.

The process of obtaining photographs with a record shutter speed was first developed by specialists of the British firm Dunlop. They managed to reduce the time during which the camera lens is opened to expose the light to the photosensitive photographic layer to a negligible value. Photographs taken with such exposure allow researchers to view natural phenomena in a different way, captured in a form that is unusual for our eyes. For example, a shot from a weapon or the contact of a flying ball with the net of a tennis racket. Now specialists can calculate with extreme accuracy the mechanical stress that occurs when the ball is hit, determine the optimal elasticity of the mesh and much more.

Viktor Karlovich Bulla took excellent reportage pictures from the theater of military operations.

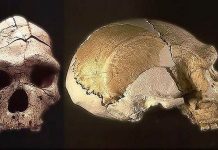

The first black-and-white camera in Russia was made in 1940. To take a picture, the photographer had to aim the lens for 20 minutes. The first color photograph was printed in the “Notes of the Russian Technical Society” in the August 1908 issue. The photo, made by chemist Sergei Prokudin-Gorsky, depicted Leo Tolstoy.

In the last century, a super camera was designed by order of a railway company in Chicago. The background to the creation of this design is as follows. Chicagoans built the most comfortable train at that time. But contrary to the company’s idea, the “train of the century” for unknown reasons was not sent to the World Exhibition of technology in Paris. Then the construction managers decided to capture the luxurious full-length train at least in a photo and send it to the exhibition for public viewing.

120 kg of a mixture of glue and rubber was spent on the manufacture of the movable part of the chamber. The camera was so huge that the photographer could freely sit inside it, almost like at home. To take photographs, the master needed at least 15 assistants. This giant, who took a single picture, is perhaps the most curious photo invention.

In 1959, Rolls-Royce manufactured an even larger camera. The weight of the record holder is about 30 tons. The length reaches 10m 68 cm, height -2m 69 cm, and width – 2m 51 cm. In 1971, the camera was significantly improved, and its cost reached 240 thousand dollars. Therefore, this camera has also become the most expensive in the world.